Treating fears and phobias

using interactive play, humor, and unbundling combined with

Gradual Incorporation of the feared thing

Karen Levine, Ph.D. and Naomi Chedd, LMHC

2023 Karen@drkarenlevine.com

. . . .

Many young children, neurodivergent and neurotypical, have fears that can cause them, and their loved ones, enormous distress. Some childhood fears simply resolve with time, development and experience. Other fears linger and interfere with the child’s well-being, or cause them to not be able to participate in everyday activities that would otherwise be highly pleasurable or meaningful, or that are needed for their health. Children who are overall more anxious, and children with fewer social and communication capacities are more likely to have fears that don’t simply resolve over time, and then some kind of treatment can be warranted.

This play-based approach to helping children resolve fears is applicable for a broad range of fears, including but not limited to the following: medical procedure-related (e.g., shots, blood pressure readings), sound related, (e.g., hand dryers, vacuum cleaners, toilet flushing, applause, balloons, thunderstorms, fireworks, alarms, others singing), touch or movement-related (e.g., escalators, elevators, bugs, clothing items) perfection related (e.g., being late, making mistakes), or unique fears (e.g. around a particular picture, character, person, or object). Children who enjoy some form of interactive play, including pre-symbolic playful engagement, or pretend play, are all potential candidates for this approach. This approach can be done by therapists or parents. It can work especially well with therapists working closely and collaboratively together with parents. Occupational Therapists, Speech Therapists, Developmental Educators, Child Life Specialists, and Mental Health clinicians may all find this approach applicable.

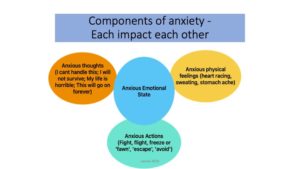

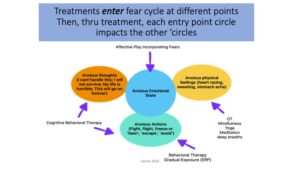

The adult combines playful, engaging child-centered play with “Gradual Incorporation” of elements of the feared object or experience. In this model, the degree of incorporation, how real, and what components are included, are based on the child’s affect. If the child starts to look scared, the adult uses less reality and/or more playfulness. With gradual incorporation, the child of course does experience more and more of the feared object, which is also what happens in gradual exposure. “Gradual exposure,” is the traditional term used for getting closer and closer to the child’s trigger, the object or situation that elicits fear. Gradual exposure is a key component of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT), the primary evidence-based treatment used to treat anxiety. Gradual exposure and gradual incorporation both involve the child gradually experiencing more of the feared thing but we prefer the term ‘Incorporation’ as it is more description of the active, collaborative process we use in this model.

With Gradual Incorporation, a child afraid of getting a shot might first play with syringes without a needle and pretend to give the adult shots, or if that feels scary the child and adult might fill the syringes with colored water and ‘squirt’ each other’s arms playfully or if that is too scary, they might squirt colored water from the syringes into a big bowl of water. Eventually, the adult might give the child pretend shots, maybe watch videos of family members getting shots, go with a family member who is getting a shot, and so on. Each step in this process more closely approximates the real thing, that is, getting a real shot in a real doctor’s office. As the child plays through each step without distress, the next step becomes easier. So, climbing the fear ladder is a gradual and fun process.

I think of two slider bars, one as humor-playfulness and the other as degree of incorporation of the feared object/experience. The adult continually tinkers with these two bars, while monitoring the child’s affect. Are they having fun? Can we incorporate the feared thing more? Can I make it more fun for the child?

Playing with Fear-of-Fear:

Often children with phobias are also ‘afraid of being afraid’ as this feeling has been so overwhelming to them. Gradual incorporation of (pretend) fear itself is part of this model. The adult pretends to be afraid or has their figure/doll pretend to be afraid, in clearly playful ways, as the child gives them ‘100 shots’ or pretends to wash their hair or pretends to startle them by activating the toy fire alarm, or shows them a scary picture. The adult also varies the playing out of fear based on the child’s affect. Is the child finding this funny? Is the child interested? Is the child looking afraid? The adult adjusts by varying the nature and intensity of pretend fear depending on the child’s affect. The adult might have their figure be so afraid they ‘jump upside down’ or ‘jump to the ceiling’ or ‘dive under a tissue box’ or pretend to ‘eat a spoon’, depending on what the child finds interesting and funny. The doll then peeks out again and the child may playfully scare them again with the feared thing. This kind of play is a way of bringing the emotion of fear into the interaction with an empathic, but not scary tone. The adult’s message through play is ‘This is how scary it can feel, right’? The adult is not pretending it is not scary, is not telling the child not to be afraid. When the adult gets it right for this child, the child, ideally feels heard, understood, and feels that ‘Yes that is how terribly scary it feels’. As they play out this fear, the child’s past experiences of fear are ‘talked about’ empathically, and no longer overwhelming. The ‘subtext’ of the play around fear is:

“That thing/event used to feel super scary! It felt terrible to be that scared! And now we are looking back on scared from these fun interactions together where we’re not scared now, we’re OK!”

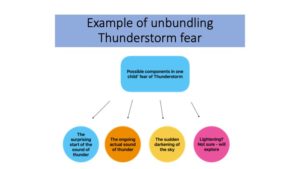

“Unbundling”: is a term we coined (Levine and Chedd, 2015) to refer to investigating and identifying key components of a fear source and using gradual incorporation to the different components separately.

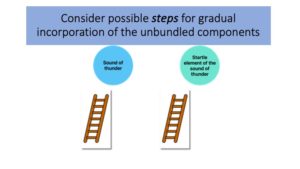

Coming up with just enough “in-between” steps of Gradual Incorporation is often what makes this process – and the treatment — both pleasant and successful. The child experiences each rung of the ladder without becoming too anxious. Many phobia sources, though, are simply too stress-inducing for the child, even when incorporation is very gradual. A child afraid of having their hair washed may begin shaking and shrieking when getting near the bathtub – or even hearing the word, bath, mentioned; a child afraid of medical procedures may begin screaming upon entering the doctor’s office or even turning into the parking lot. Separating out, and unbundling, the components of hair washing might involve the elements of being in the tub, having shampoo on head, rinsing head with water, and towel-drying hair. The adult constructs different Gradual Incorporation fear ladders for each component, separately and eventually together. For example, pretending to wash the child’s hair (or a doll’s hair) at the breakfast table, then washing “one hair” of oneself, a stuffed animal, then the child (this is easy to make very funny!) with real shampoo during this kind of play time, are less threatening to incorporate, far from the real hair-washing-in-the-bathtub experience. This play can then be expanded to include washing a doll’s hair in an empty tub, play-washing the child’s hair with clothes on and no water, and gradually creating closer approximations to the real thing, combining these elements. As the play progresses, the adult becomes more able to identify the specific aspects of hair washing (fear of soap getting in one’s eyes, fear of the water being too hot, fear of water covering the child’s nose/mouth making it hard to breathe) that create anxiety and can play through each in fun or silly ways. Through this playful gradual incorporation, the child gets used to these elements of hair washing bit by bit, while experiencing the play with the adult as pleasurable.

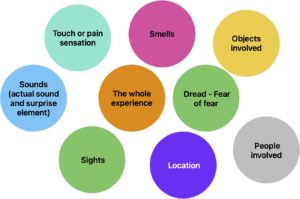

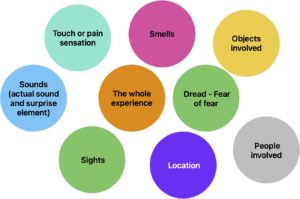

Unbundling elements to consider are pictured below. Not every fear source has every element. Some elements are key for some children/fears, while other elements are for other children/fears.

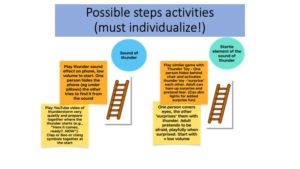

Unbundling fear of hand dryers (and other sound-related phobias such as thunder, alarms, and fans) often involves fear of the actual sound and fear of the surprise/startle element of the sound when the hand dryer starts unexpectedly. For many children, this may expand to include fear of going in public bathrooms. Fear of being in the school cafeteria at lunch may involve fear of the noise, the crowds, and rapid, unpredictable movement of children, maybe loudspeaker announcements at lunch, and possibly the smells. (Really, who in the world has positive memories of the school cafeteria?!) Fear of insects may spread to fear of butterflies, birds, anything that flies, or even going outside once the weather gets warm. The surprise appearance of bugs visually, the tickling on the skin, and fears around sensations of getting stung may all be components to work on.

Unbundling and working on the gradual incorporation of fear ladders to individual components of the fear, sometimes one at a time, sometimes a few at a time, can make the entire process much more manageable for the child for whom even a small amount of the whole fear is too distressing. Ultimately, it can lead to lessening anxiety, and sometimes, a complete victory, overcoming the phobia.

Humor:

Is a useful tool in treating many fears in young children. By “humor” we’re referring to playfulness used by the adult with the child in an individualized manner that the child finds funny. For instance, adult and child with a phobia of bugs together make their Spiderman figures noisily stomp out plastic bugs and throw them in a pretend (or real) trash can. The goal is to get the child to smile, even laugh, connect with and feel supported by the adult and share affect and the entire experience. This is part of treating the child — and a typical example of this kind of humor. It is different from ‘performance humor’ of Knock-Knock jokes or wearing funny hats – although they both sometimes have their place in treating phobias.

Humor can be readily incorporated into the process of gradual incorporation. With my colleague Naomi Chedd, LMHC, I wrote about this in detail regarding children with anxiety who also have developmental challenges such as ASD in our book Attacking Anxiety (Jessica Kingsley Publishers, 2015). The approach is the same, highly individualized process, whether or not the child has other cognitive, physical or emotional challenges: combining gradual incorporation with playful engagement, adult support and attentiveness and a great deal of child control.

While there has been very little research on the impact of uses of humor, we know from our own experiences as we work and play with young children, that in general, humor, that is, playful engaging child-attuned humor, often has the following properties that make it especially useful in this process:

1. Playful engagement often reduces the intensity of the experience of anxiety: When a child is in a playful engaged state, they generally are not simultaneously experiencing a high level of anxiety. Getting a child into a playful state before and during situations that are likely to cause anxiety, when this is feasible, can often be very effective in helping the child stay regulated and reducing anxiety.

2. Playful interaction makes activities and relationships more fun for children, even when they are anxiety-provoking or difficult. Working with children on issues that cause them anxiety is hard and, yes, potentially anxiety-provoking work for adult and child. However, insuring there is a great deal of fun built into the work increases the child’s pleasure in participating.

3. Playfulness and humor can be used across various environments such as home and school, with children of various ages, and with various developmental profiles. Once a parent or clinician learns how to engage a particular child in humor and learns what that child finds funny and interesting, they can communicate this to other adults working with the child on their fears.

A word of caution: There are some circumstances and ways in which we should not use humor:

1. Never use humor to tease the child in a way that insults or belittles them or makes them uncomfortable.

2. Do not use humor when a child is showing a great deal of distress, sadness or anger.

3. Do not use humor in a way that overwhelms the child and the child becomes either over-the-top giddy or frightened. Using slower, less emotionally and affectively loud humor that involves the child more may be palatable – and effective.

4. Some children seem to not have much of a sense of humor at some points in their development. Don’t force it. But don’t be afraid to introduce small amounts of it from time to time. Helping a child develop more of a sense of humor can lead to many gratifying moments for the child and their family and friends.

5. Humor is quite culturally variable, culturally specific, family (parent) specific, and child-specific. If you are a clinician working with a child it is key to learn about the family’s cultural humor style, observe parents and child playing together, and asking parents directly.

Hand-Dryer example:

I tried to treat several children who were afraid of loud, automatic hand dryers, first by showing them videos and then trying to ease them into the bathroom in our building which has a hand dryer, which happens to be particularly noisy and objectionable, even for reasonably mature and well-balanced adults. However, even with some preliminary, playful treatment, going into the bathroom was still too anxiety-provoking for some children, too big a step on the ladder of gradual incorporation.

I further refined the process and built in additional steps in between watching a video and going into the bathroom: I bought a real hand dryer so I could play with it with the children in my office, starting with having it on the floor unplugged, pretending it made sounds, pretending the children or the stuffed animals or I found it too loud. Some children wanted to pretend to scare me, pretending to start the hand dryer is I covered my ears, ducked behind the couch then popped up again only for them to do this again, laughing.

With several children we watched a video of the hand dryer, with the volume first very low. Some children started the video while I pretended to be scared. As the children got used to it, I put the volume a little higher and they continued to ‘scare me’, also getting used to the startle and the sound, at the same time.

Then I plugged the hand dryer in, in our playroom adjoining my office, where the children could peek in as I turned it on and played with it in various ways, myself, making it propel a toy truck across the floor, blow crumpled paper up in the air, blow balloons out of the play tunnel, and pretending to dry and style my hair like it was a hairdryer. Sometimes I pretended to be afraid when I activated it, exaggerating my affect and providing all the appropriate sound effects for children who found that funny.

Eventually all of the children chose to join me in this hand dryer play. After experiencing this kind of play in the comfort and familiarity of our playroom, they were much less fearful when they entered the bathroom. Several showed no fear whatsoever and all eventually went into the bathroom calmly and comfortably. Playing with the real hand dryer in the office first meant I could add many new steps to the Gradual Incorporation ladder, each with its own novel and fun/funny components.

Step-by-Step Summary

1. Pick a single fear to work on, to start with.

Many kids have many fears but pick just one to start working. As you start with this one, you and the child will be learning just what works with them, and can use what you learn to work on other fears. Pick a fear that is problematic/interfering and also that is a relatively easier to work on, one that you can both easily access and you can control the unbundled components of it, the ‘dose’ of it, easily. While how challenging or easy a fear will be to work on depends on the child and what elements of the feared thing are key for them, the list below may give a starting place for considering the sorts of fears that tend to be easier to start with.

Easier fears to work on usually

-

Riding in the car,

-

Haircuts, baths, nail clipping, teeth-brushing, hair brushing

-

Happy Birthday Song,

-

Fire alarms

-

Hand dryers

-

Thunder

-

Clothing related

-

Bugs

-

Elevators/escalators

-

Germs

-

Characters/scenes in books or videos

Middle level of difficulty fears to work on, usually

-

Doctor visit – specific procedures

-

Flying in airplane

-

Bowel movements

-

Dogs

-

Vomiting

-

Eating related

Harder fears to work on, usually

-

Infinity/end of the world

-

Death (not usually one for this approach)

-

Illness in self or others

-

Going to school (usually many factors)

2. Unbundle the fear into components to work with

Consider the elements of the fear from the colored circles below and the colored circles in the section on Unbundling.

3. Design steps for gradual incorporation into play of each of the components.

Start with a step that is interesting/fun and not at all scary to the child, gradually incorporating bits of the previously scary element(s). The ideas in the Appendix may be helpful. While some planning ahead is useful for gathering materials and having concrete ideas at the ready, in this model the specific activities of the steps evolve and shift as you play, following the lead of what the child is interested in, finds fun or funny. If the child starts to become afraid, add more playfulness and backup steps until the child is having fun again. You will most likely modify, skip, combine or add steps based on the child’s responses.

4. Eventually collapse the steps and the child is doing the feared thing!

Of course, this may involve some planning if the feared thing happens outside of the home (e.g., a fire drill at school; procedure at a doctor’s visit). It can be useful to bring some video clips of this fun playful step play to the feared event (Bring video of some hilarious doctor play to ‘show the doctor’ at the visit), and to do some play at the event when this is possible. Sometimes we adults think the child is ready but they are still fearful around the event and we can go back and do some more work on the Steps and consider if there are elements we have not included in our play, some more steps to add.

☺ ☺ ☺ ☺

In conclusion,

We have found that children are generally highly motivated to overcome their fears. Using playful humorous interactions, co-regulation, unbundling the source of the fear, and playing around with fear of fear, in combination, can be a highly effective set of tools while engaging the child in gradual incorporation of the thing or situation they are afraid of.

For more information on Williams Syndrome:

We have published some exciting preliminary results of using this approach in children with Williams Syndrome:

Bonita P. Klein-Tasman, Brianna N. Young, Karen Levine, Kenia Rivera, Elizabeth J. Miecielica, Brianna D. Yund & Sydni E. French (2021): Acceptability and Effectiveness of Humor- and Play-Infused Exposure Therapy for Fears in Williams Syndrome, Evidence-Based Practice in Child and Adolescent Mental Health

Klein-Tasman, B., Young, B., and Levine, K. (2023) Addressing Fears of Children with Williams Syndrome: Therapist and Child Behavior in the Context of a Novel Play-and Humor-Infused Exposure Therapy Approach. Frontiers DOI: 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1098449

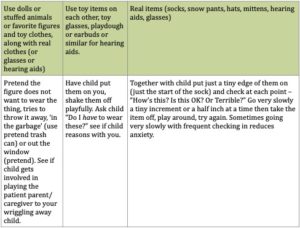

Appendix: Examples for unbundling and gradual incorporation around specific fear sources

For each of several common fears, materials are in green in the charts below, and sample activities described underneath. Throughout doing the activities, the goal is to keep the play fun and funny, and for the child not to be distressed or scared as you gradually incorporate materials and activities related to the child’s fears. Stay attuned to the child’s affect and shift play to more fun/funny and less realistic, if you start to see signs of distress.

If you know what aspect is scary to the child you may be able to unbundle and primarily do play that focuses on that aspect (e.g., sound; touch, etc.).

For some children the play will be more sophisticated with more language, pretend play, and complicated humor and for others the play with be directly with the materials, not with pretend figures, and the humor simple, modifying for whatever resonates with that particular child. Easy access humor tends to work best to sustain a relaxed playful emotional state and tone between you and the child. The materials, activities, pacing, and style need to be fully individualized for each child and situation. In this model you let steps evolve and shift as you play, following the lead of what the child is interested in, finds fun or funny. If the child starts to become afraid, add more playfulness and back up steps until the child is having fun again. These play ideas below are not meant as recipes to follow, rather, as samplers to help spark your own creativity!

Injections (Shots)

Clothing items (socks, snow pants, shoes, hats) or glasses or hearing aids

Figure or character (e.g. from book or video)

Our Authors:

Karen Levine, PhD, Lecturer on Psychiatry Harvard Medical School (part-time), is a practicing psychologist formerly in MA, now in Maine. She was the co-founder and co-director of the Autism program at Boston Children’s Hospital in the 1990s. With Naomi Chedd, she authored three books including Attacking Anxiety (JKP, 2015). She is the recipient of numerous awards including the 2000 Award for Excellence from the Boston Institute for the Development of Infants and Parents (BIDIP). She is a Clinical Consultant to the ICDL. She specializes in joyful, individualized, relationship-based approaches for anxiety with young neurotypical and neurodivergent children.

Naomi Angoff Chedd, LMHC, is a licensed mental health counselor. For the past 25 years, she has worked with young children, adolescents, and young adults with autism spectrum disorders and other developmental disabilities, anxiety, depression, and other mental health challenges and consulted with schools and families on programming and services. She is the author of many articles on behavioral health challenges and solutions and is co-author with Karen Levine, PhD. of three books. Currently, Naomi serves as the Director of Counselor Support Services, for Counslr, a telemental health company serving high school and college students and working professionals.

Enter the text or HTML code here